When Ace folded up in late 1962, Pablo S. Gomez was already one of the big names in the Philippine komiks industry. He had a big following of readers who anticipated his new stories and serials.

To house his new company, Gomez alloted one portion of his house in Sampaloc as temporary office of the PSG Publications.

As a veteran komiks writer, Gomez knew some of the best komiks illustrators and writers and he hired them as regular contributors to PSG, such as Mars Ravelo (who used his pseudonym Virgo Villa), Francisco Coching, Nestor Redondo, and Alfredo Alcala.

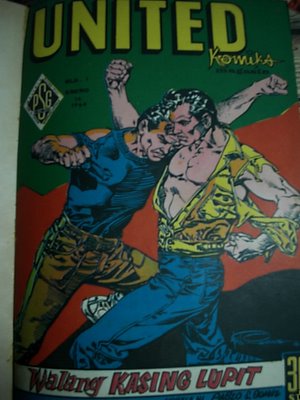

United Komiks #1. Cover art by Francisco V. Coching, by then the most popular artist in Philippine komiks.

The first komiks-magazine of PSG Publications was United Komiks, the first number of which was reeased on January 1964.

As a prolific writer, Gomez could capitalize on his voluminous unpublished scripts (plus the ones brewing in his head) and thus economize on writers 'fees. For instance in one komiks-magazine there were at least two or three stories or serials written by him although he sometimes used Rene Rosales as a pseudonym. The technique worked, and many komiks readers became fans of Rene Rosales as well, not knowing that Rosales and Gomez were just one and the same.

Gomez also tapped the talent of his younger brother Daddie Gomez, who was in his own right also a talented writer. Daddie sometimes used the pen name Tennessee Francel, and D. G. Salonga, which is a play of his actual name Dominador Salonga Gomez.

The United Komiks was a bestseller. It competed fiercely with the numerous komiks titles that proliferated at that time, such as those published by Bulaklak, GMS, Philippine Education Company, and even GASI (the new komiks company of the Roces clan). The only advantage of GASI from its competitors was its komiks-magazines’ efficient distribution even to the very far provinces. Some of the most anticipated serials in the United Komiks were Mars Ravelo’s Optarza, Dyangga, and Gapang sa Lusak, while Gomez contributed with his Timbuktu, Tsandu, Triple, and Danny Boy.

But perhaps the most successful feature that boosted the sales of the United Komiks was “Mga Kuwento ni Bruhilda”, a series magically illustrated by the young Alex Nino. Previously rejected by local komiks editors who could not understand his genius, Nino was rediscovered by Gomez, who gave the former regular assignments in the PSG. Indeed, Gomez saved a genius from anonymity and obscurity.

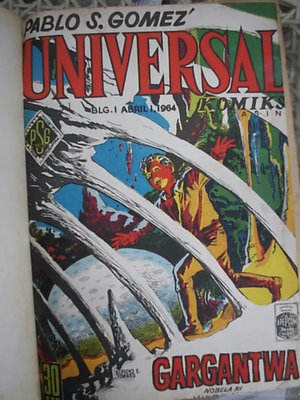

The over-all sales of the United Komiks were encouraging enough to Gomez, who decided to publish an additional komiks-magazine: the Universal Komiks. It was released on April of 1964

Universal Komiks #1. Cover art by Elpidio Torres.

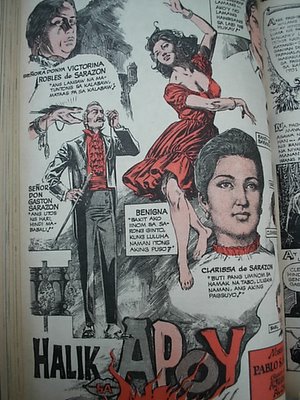

The Universal Komiks was another PSG bestseller. Some of its popular series were Mars Ravelo’s Devil Boy and Gomez’ Taong Buwaya and Halik sa Apoy and Rico Bello Omagap's Uhaw sa Dugo.

Halik Sa Apoy serial novel in the Universal Komiks. Story by Pablo S. Gomez. Illustrated by Alfredo Alcala.

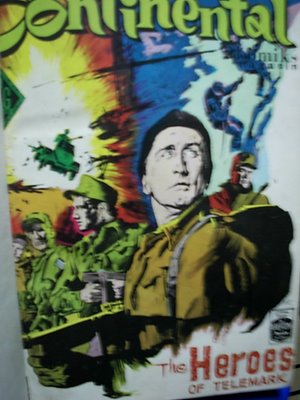

The third komiks-magazine of PSG Publications was Continental Komiks, launched in 1965. Like the other two titles before it, the Continental Komiks became a bestseller among komiks readers. The Continental featured short stories by such veteran writers as Rene Villaroman, Greg Igna de Dios Tony Tenorio, and Rico Bello Omagap.

Continental Komiks #1. Cover Art by Nestor P. Redondo

Gomez eventually hired Tenorio to take charge of the full editorship of his komiks-magazines.

At around this time, a young man was introduced by Tenorio to Gomez. His name was Carlo J. Caparas, a security guard who showed a talent for writing. Gomez was impressed with the story submitted by Caparas, and from then on the young man became a regular PSG contributor. A few years later and Caparas would make a name for himself for his komiks serials Panday, Pieta, Citadel, and many others that became successful movies. Yet, it should always be remembered that it was Gomez who discovered his talent and gave him a break in the Philippine komiks industry.

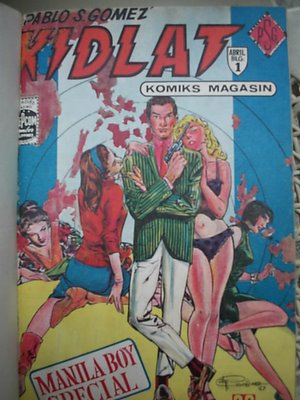

Kidlat Komiks #1. Cover Art by Francisco V. Coching.

The success of his earlier titles prompted Gomez to publish another komiks-magazine in 1967. Entitled Kidlat Komiks, this was another bestseller that became a favorite of the masses. At about this time, Gomez transferred his office to a big compound in the corner of Aurora Boulevard and Balete Street in Quezon City. Christened the “White House” because of the big white edifice in the property, this new building was the solid proof of Gomez’ success as a komiks publisher.

Because of his popularity as a movie and komiks writer, Gomez became a close friend of many movie stars among them the young stars Fernando Poe Jr ., and Susan Roces. Gomez and Roces were personal confidants to each other, even before the latter’s engagement to the young Fernando Poe. Gomez even featured the love story of Susan Roces and Fernado Poe Jr, in a section in the United Komiks entitled “Mga Lihim ni Susan Roces”. It was a delight not only to komiks fans but to movie fans as well. Even now some forty years since they first met, the two regularly visit each other.

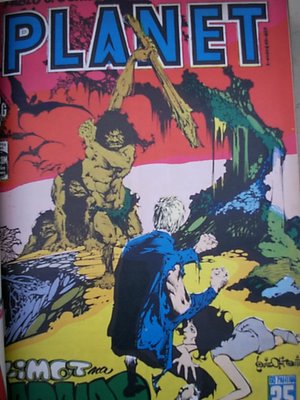

An early issue of Planet Komiks. Cover art by Alex Nino, who signed the art "Louie Chito", his firstborn son.

In 1968, another PSG komiks-magazine was born entitled Planet Komiks, a komiks-magazine that mostly featured fantasy and science fiction stories and serials. It was a highly artistic komiks-magazine, with some of the big names in komiks art contributing, such as Alex Nino, Alfredo Alcala and Nestor Redondo.

The PSG Publications, however, was hit hard by the decline of komiks readership in the late 1960s. This was partly due to the proliferation of several komiks-magazines that flooded the newsstands. Komiks readers just got somewhat overwhelmed. This decline could be considered as an implosion, a self-destruction. The booming industry killed itself.

Yet, according to Gomez (when I interviewed him), the most significant factor that led to the industry’s decline was the proliferation of the Bomba or smut komiks. This idea was seconded by Hal Santiago, then PSG Komiks’ resident artist. Apparently, the fly-by-night Bomba Komiks which sold as cheap as the clean-type komiks, captured the attention of male local readers.

Most importantly, some people equated the Bomba Komiks to the clean-type ones which got the stigma as well. Komiks was forbidden in many homes because of this stigma.

Says Pablo: “Pati kaming mga malilinis na komiks ay nadamay sa mga Bomba Komiks na yan, kasi ang akala ng mga tao lahat na ng komiks ay may mga litrato o drowing na Bomba”.

Then, in 1972, President Marcos declared Martial Law. Severe censorship followed. Sure it killed the Bomba Komiks, but it also killed the clean-type ones. The regime forced komiks publishers to use cheap and inferior local papers in komiks printing. Hal Santiago laments, “This kind of paper was of the cheapest quality. You could hardly appreciate the komiks after the printing. How can you expect people to buy them?”

PSG Publications indeed suffered irreversible losses after these unfortunate events. Gomez who mostly got his initial funds through personal loans, was forced to sell his titles to his rival komiks company, the Affiliated Publications, Inc., another company of the Roces clan.

Yet, this was not the end of Gomez’ career in komiks, for the best years were still ahead of him. There would be more big novels to come, especially in the late 1970s and the whole of 1980s. Indeed, a good and talented man is very hard to put down.

This then is the story of PSG Publications, one of the most colorful komiks company of the once thriving Philippine komiks industry.

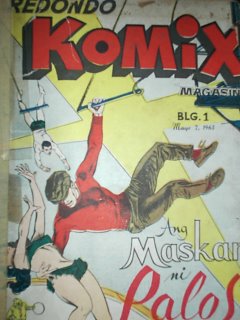

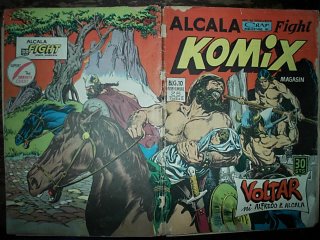

This short story that appeared in the issue #12 of Redondo Komix was a unique example of experimentations by CRAF'S creative team. Why? Because this was literally illustrated by CRAF,that is, by Caravana, Castrillo, Redondo, Alcala, and Francisco. Each panel had a touch of ink by each of these artists.

This short story that appeared in the issue #12 of Redondo Komix was a unique example of experimentations by CRAF'S creative team. Why? Because this was literally illustrated by CRAF,that is, by Caravana, Castrillo, Redondo, Alcala, and Francisco. Each panel had a touch of ink by each of these artists. Kislap Magazine 1951, showing Kenkoy movie on the cover.Author's collection

Kislap Magazine 1951, showing Kenkoy movie on the cover.Author's collection Reyna Bandida by Virgilio and Nestor Redondo

Reyna Bandida by Virgilio and Nestor Redondo Pilipino Komiks with Bondying Cover by Elpidio Torres

Pilipino Komiks with Bondying Cover by Elpidio Torres DI-13 by Damy Velasquez and Jesse Santos

DI-13 by Damy Velasquez and Jesse Santos

Issue#8 of the short-lived Halakhak Komiks. Two issues later, it closed publications.

Issue#8 of the short-lived Halakhak Komiks. Two issues later, it closed publications.