The comics pages that we hold in our hands are literally artworks that have been printed on paper. Prior to printing, these comics pages are known as original comic art, expertly drawn by the illustrator to visualize the writer’s story.

The standard original art is a bristol board with the usual size of 11x14 inches. In Philippine comics, a story (wakasan) is usually four to five pages in length (The serial-or itutuloy- is also usually divided into four or five-page parts)

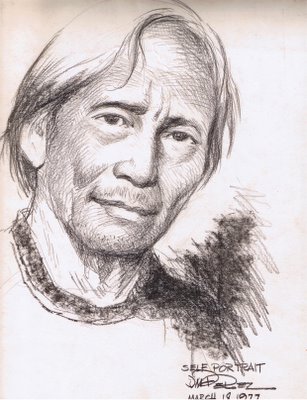

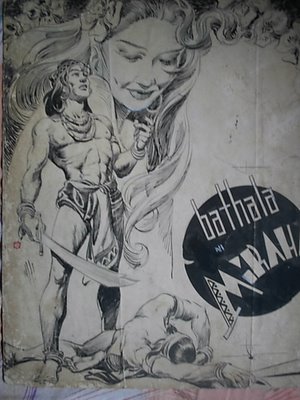

The cover art is usually the most special page in the comics. The great Francisco V. Coching was a favorite cover illustrator because of his dynamic compositional skills. A Francisco V. Coching Original Cover Art for a 1948 issue of the Liwayway Magazine

A Francisco V. Coching Original Cover Art for a 1948 issue of the Liwayway Magazine

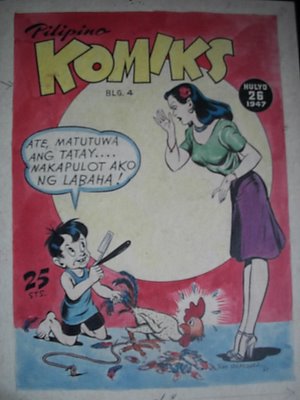

The only known surviving original cover art of Pilipino Komiks. Tony Velasquez, Pilipino Komiks#4, 1947.

The only known surviving original cover art of Pilipino Komiks. Tony Velasquez, Pilipino Komiks#4, 1947.

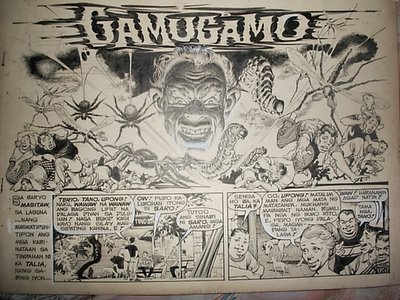

The opening page, with the story’s title, and wherein the writer’s and artist’s name were written, is known as the splash page. Traditionally, this page contained at least one big panel occupying at least half the size of the page, and two or more smaller panels, or something similar. Alex Nino Splash Page for "Gamu-Gamo" story by Tony Velasquez, 1966. This is the earliest known existing original of Alex Nino.

Alex Nino Splash Page for "Gamu-Gamo" story by Tony Velasquez, 1966. This is the earliest known existing original of Alex Nino.

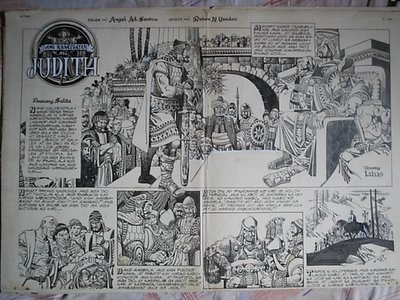

Sometimes, the illustrator would utilize two of the opening pages for one spectacular illustration. These two-in-one page is called the double splash page. Alfredo Alcala, Hal Santiago, and Ruben Yandoc are fine examples of artists who had done this particular panoramic page.  A super double splash page by Ruben "Rubeny" Yandoc for his memorable "Bible" iseries that appeared in Kenkoy Komiks in early 1960s.

A super double splash page by Ruben "Rubeny" Yandoc for his memorable "Bible" iseries that appeared in Kenkoy Komiks in early 1960s.

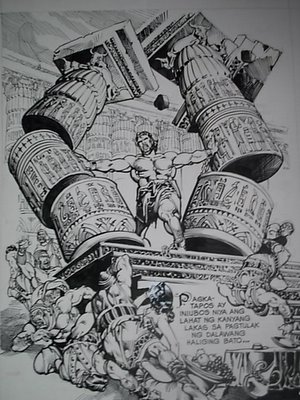

A splash page, however, is not only limited to the opening page. Sometimes an artist would make a splash page from any one of the inner pages to emphasize a particular part of the story.  For instance, the page above by the great artist Emil Rodriguez is supposed to be a panel page, but since he wanted to emphasize Samson’s destruction of himself and his enemies, he turned the page into a big one panel splash page.

For instance, the page above by the great artist Emil Rodriguez is supposed to be a panel page, but since he wanted to emphasize Samson’s destruction of himself and his enemies, he turned the page into a big one panel splash page.

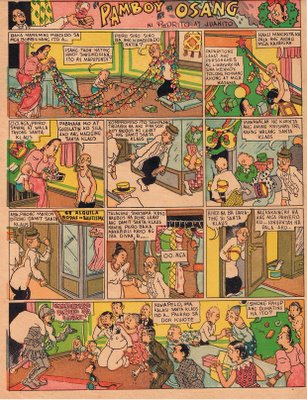

The following pages after the splash page are called panel pages. They consist, of course, of panel drawings chronologically arranged to tell a story. ![]() Francisco V. Coching is one of the first Filipino comic artists to design inner pages with ingeniously designed panels, like this page from his early Marabini serial novel.

Francisco V. Coching is one of the first Filipino comic artists to design inner pages with ingeniously designed panels, like this page from his early Marabini serial novel.

Comic Art as a Legitimate Art Form

In the United States and Europe, where comics is regarded as legitimate art form, collecting original comic art is a long and valued tradition. Many collectors even set up festivals and conventions to trade original comic art and comics.

In the Philippines, very few collect original comic art. In my experience as a collector and researcher, I found that these very few collectors are actually comics artists themselves who wanted to get a closer look at the rendering of their favorite fellow illustrator. I found that among artists, two great masters are often collected and imitated: Francisco V. Coching and Nestor P. Redondo. This is not surprising because they are considered the two finest illustrators in the history of Philippine comic art.

In the Philippines where comics is very popular among the lower classes of society, original comic art is considered a virtual no rich collector’s item. Filipino art connoisseurs shun the original comic art as not in their regular collecting menu.

Over the past few years, however, this began to change. The awareness of the Filipinos’ great contribution to comic art led to an increasing appreciation of the original comic art as a legitimate art form. Some art collectors who had collected American comics realized that many several of these comics were illustrated by Filipinos. Conan the Barbarian, Spider-Man, Vampirella, Batman, the Swamp Thing, Superman, have indeed been illustrated at one time or another, by Filipinos, and their names appear on the credit pages: Redondo, Nino, Alcala, Nebres, and many more. This appreciation led to a rediscovery of a vast body of work in Philippine comics hitherto unappreciated by art collectors.

This began a few years ago when I decided to test the market for original art by selling some pages on the internet. To my knowledge, no one had ever sold Filipino comic art before in the internet. Although DC and Marvel originals of Nino, Alcala, and Redondo were known to fetch high prices in auctions, their Filipino comic artworks were virtually unknown among foreign collectors.

I thought that selling a few of my originals in the internet would spark some curiosity, because these artists’ works in Filipino comics are no less masterful than their foreign artworks(in fact I sincerely believed that Nestor Redondo and Alfredo Alcala reached the pinnacle of their drawing prowess even years prior to their first work in DC comics). Perhaps this curiosity would later turn into appreciation of the greatness of Filipino contribution to comic art. The long overdue appreciation for our local comic artists would certainly follow. In a few years, we may be awarding the National Artist award to one of our comics artists.

I am very happy that now, a few serious art collectors are entering the field of collecting original comic art. Now and then, I receive emails from these few collectors asking me if I could sell them an original page each by our great comics artists. Often, I would abide by their request if I see that I could part away with some without my feelings being hurt.

Although during the past years I have been able to collect some 1,500 pages of original comic art, I am by no means a hoard. I wanted to share it with other collectors. I wanted to give way to new collectors.

In fact, I was starting my prices in auction at one dollar per page without reserve because I wanted even the new or average collector to purchase original Filipino comic art at a price he can afford. There are many who made a bargain, winning some pages for as little as four or five dollars each. I am happy whenever I sell an original to an appreciative new collector.

Although there were a few Filipinos who purchased original Filipino comic art in my auctions, the majority of buyers were foreigners, comic art collectors from the United States and Europe. Not surprisingly, a particular favorite in auctions were the works of Alex Nino, Nestor Redondo and Alfredo Alcala, because they were the top three Filipino illustrators in DC and Marvel comics. Could it be that foreigners are more appreciative of our local artists’ works rather than our fellow Filipinos? Or maybe we have a little more to learn to appreciate comic art.

The Pioneer Collectors of Philippine Comic Art

Even prior to the present generation of comic art collectors, there were already a few who valued and collected Filipino comic art. They were Orvy Jundis(comics historian), Manuel Auad (comics writer and publisher), and Steve Gan(comics artist).

Orvy Jundis is known to have specialized in collecting Alex Nino art, while Manuel Auad is known to have specialized in collecting Redondo and Alfredo Alcala. A glimpse of Auad’s magnificent collection can be seen featured in the Comic Book Artist Magazine #4.

Steve Gan’s collection is a veritable archive of Philippine comic art. There are Alex Ninos, Redondos, Cochings, Rodriguezes, Nebres, Alcalas, and many more.

It is only sad that, with the great bulk of original comic art that had been produced in the Philippines because of our rich comics tradition, only very few have survived (or been found, yet). For instance, it is now extremely hard to find an original cover art by Coching, with the exception of the few that had been kept by his family. The same goes for a Redondo or an Alcala.

Yet, with the few that we have been able to save, we must be thankful nevertheless, because they are enough proof of the high point our comics artists achieved in the field of comic art.

Part of the more than 1,000 pieces of old Tagalog Komiks found in the author's collection.

Part of the more than 1,000 pieces of old Tagalog Komiks found in the author's collection.

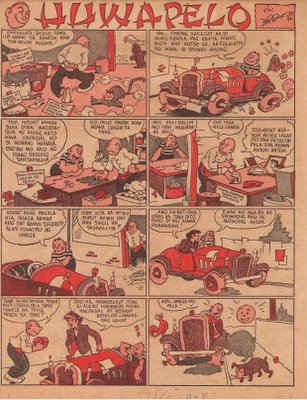

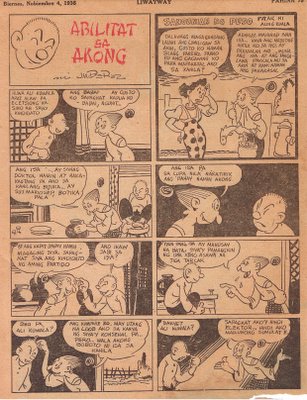

In 1935, Perez retitled Huwapelo into Abilitat sa Akong

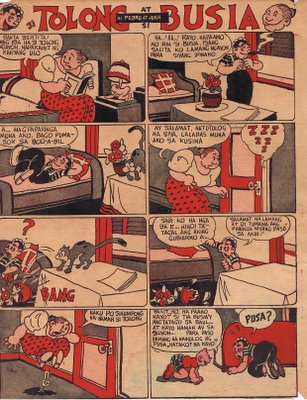

In 1935, Perez retitled Huwapelo into Abilitat sa Akong Tolong at Busia, Liwayway 1935.

Tolong at Busia, Liwayway 1935.